This is the fifth post in our special series taking a closer look at the impact of Connecticut’s behavioral health workforce challenges on children and families – and exploring solutions. Read the rest of the series here.

May 23, 2024

By Aleece Kelly, MPP, Senior Associate

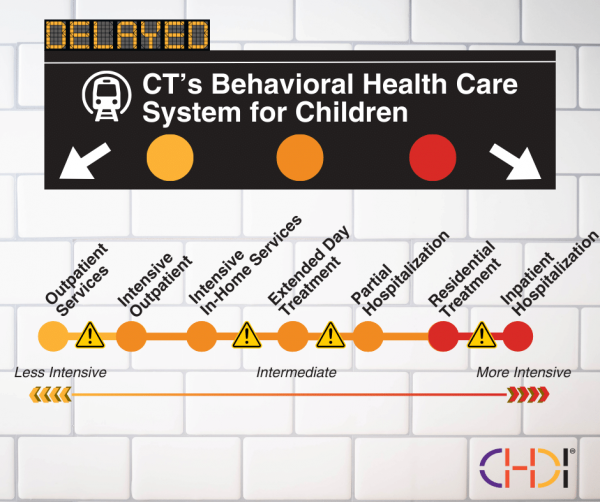

Connecticut’s behavioral health system for children offers different levels of care and services to meet a wide range of concerns, diagnoses, and acuity. These levels of care range from less intensive options, like outpatient therapy, to more intensive options, like inpatient hospitalization.

Imagine that the various levels of care within the children’s behavioral health system are stops on a subway line, with some trains going uptown (needing more intensive services) and others heading downtown (ready for less intensive services). For kids and their families to have the best possible outcomes, they must have access to the level of care they need, when and where they need it.

As children’s behavioral health needs have increased since the pandemic, the system’s ability to provide well-matched, timely, and effective services – to keep the trains running on time and in the right direction, so to speak - is more critical than ever. Children and teens must be able to move “up a stop” when their symptoms are more acute, then back “down a stop” as symptoms improve. The stops in the middle of the line are what we refer to as intermediate levels of care.

Unfortunately, as we detailed in a strategic plan published last year, this increased need for behavioral health services has come at a time of unprecedented, nationwide workforce* shortages in the behavioral health field, largely due to years of chronic underfunding. Programs are struggling to operate at full capacity and many services have long waitlists. Many outpatient clinics have lost their most experienced staff, replacing them with qualified but less-experienced clinicians not prepared to handle the higher acuity levels among children waiting for intermediate levels of care. This causes bottlenecks across the system, impeding the flow of traffic between outpatient, intermediate, and intensive levels of care.

Intermediate levels of care (ILCs) are center- and home-based programs that provide more frequent treatment sessions than typical outpatient care but are less intensive than inpatient hospitalization, enabling youth to stay at home with their families as they engage in treatment. They typically provide a combination of individual therapy, group therapy, recreational activities and/or art therapy, and family therapy. Because of their central place on the care continuum, delays at intermediate levels of care have a particularly widespread, systemic impact.

ILCs include center-based and in-home services, such as:

ILC programs for children in Connecticut are center-based, with more than sixty such programs statewide. Earlier this year, my colleagues Jason Lang, Ph.D (CHDI), Amber Childs, Ph.D (Yale University School of Medicine), and I co-authored a report on center-based ILCs, which found that Connecticut’s programs generally align with accepted care guidelines and best practices. However, we also found that demand for ILC services is outpacing availability. The Connecticut ILCs we surveyed reported that their staffing levels were down by one-third on average, with average waitlists of two to six weeks.

Connecticut’s IICAPS programs, an example of in-home ILC services, are the most recent casualties of the state’s workforce and funding shortages. IICAPS already had long wait lists due to the closure of some programs. The latest cuts will inevitably result in even longer wait times for care for children and families and further increase pressure on other services across the system.

At a system level, workforce gaps and insufficient capacity in intermediate levels of care challenge the overall functioning and throughput of the children’s behavioral health system. Returning to our subway analogy, trains are trying to move up and down the track, but each stop (level of care) is already full of children, leaving no room for those on the train to get off. Meanwhile, other children and families are waiting at each stop for a train with available space.

Delays and lack of capacity can negatively impact children and heighten stress among family members and providers. For example, a child’s symptoms may worsen while awaiting intake or remaining in outpatient settings not designed for more complex needs. Additionally, outpatient clinic staff may be bogged down managing intensive cases that would be more appropriate for an ILC, leading to longer wait times for children needing outpatient services.

Melissa Jacob, LCSW, Director of Child Outpatient Services & Care Coordination at Bridges Healthcare in Milford, says that outpatient clinics like theirs have become the catchall, “holding zone” for children waiting to get into higher levels of care. “When they come to us, we’re something, but we’re not the care that they need,” Jacob says. “I always say it’s like sending a kid with a major leg injury to the dentist... It’s not the right fit.”

On the flip side, children whose symptoms have improved during inpatient hospitalization and are ready to “step down” to intermediate services may have to either stay hospitalized longer than needed, go home without adequate supports, or return to outpatient settings. It also means fewer open inpatient beds for children stuck in emergency rooms.

According to Jacob, both scenarios can be very stressful for families and providers. "I’ve been here for twenty-four years, and the system is breaking… When a kid comes in and they’re in crisis, and they have to wait three months to go to a higher level of care, [that affects] everybody below them in the system.”

To address these challenges, many behavioral health agencies must focus on staff retention and recruitment and meeting caseload demands, doing the best they can under difficult conditions to provide high-quality services. However, the situation is limiting their ability to invest significant time in quality improvement.

For example, our report on ILCs found that while these programs generally meet care guidelines, there were opportunities to use evidence-based treatments (EBTs) more consistently across ILCs, so we included recommendations related to EBT training, implementation, and quality improvement. But in reality, these recommendations will be nearly impossible to implement until providers have sustainable staffing levels. Significant quality improvement among ILC and other children’s behavioral health programs will be contingent upon addressing systemic workforce needs.

To address the specific challenges facing ILC programs, three recommendations from last year’s strategic plan to strengthen the behavioral health workforce stand out:

Nonprofit, community-based ILC programs could receive short-term relief through emergency grants from the state dedicated specifically to staff recruitment and retention. These grants should be flexible to meet provider and community needs and prioritize services with higher proportions of underserved and/or historically marginalized populations. Providers who use evidence-based, trauma-informed treatments (which have been shown to be more effective than usual treatments, especially for children and youth from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds) should also be prioritized.

In an earlier post in this series, my colleague Jack Lu, Ph.D, wrote about how Connecticut can retain children’s behavioral health providers in outpatient settings; many of his ideas are also applicable to ILCs.

In addition to making immediate investments in recruitment and retention, it is also critical that the state raise Medicaid reimbursement rates for all children’s behavioral health services, including ILCs. The state’s Department of Social Services recently published a rate study revealing significant disparities in reimbursement rates for behavioral health services when compared to similar states and other healthcare services. Nonprofit providers largely rely on reimbursement for operating costs and cannot meet salary demands to hire staff given the current rates. To maintain a highly qualified workforce that can meet children’s needs, reimbursement rates must be raised.

It was great to see the state legislature acknowledge the gap between reimbursement and actual costs in the 2024 session by allocating additional Medicaid funding for children's behavioral health and increasing grants to nonprofit providers. However, it’s a drop in the bucket compared to what is actually needed to close that gap.

To learn more about behavioral health reimbursement rates, please refer to Recommendation 1 in the Strategic Plan and read our CEO’s recent blog post.

We know that there is unmet demand for ILC services. However, because of a lack of standardized, system-wide data, we do not fully understand whether this shortfall is due to the workforce challenges, or if the state would fall short in meeting ILC demand even with higher staffing levels. The lack of systematic data collection on staffing, referrals, and wait lists has created another gap, in this case in the state’s understanding of and ability to respond proactively to systemic challenges.

A behavioral health workforce center, like those in other states like Nebraska and in other areas of the Connecticut workforce (e.g., nursing), could track trends that are currently not understood on a state-wide level. Investing in this type of infrastructure would support the state in making systematic, data-informed decisions that will strengthen system planning, programs, and services for children and families.

To learn more about the role of a workforce center, please refer to Recommendation 3 in the Strategic Plan.

Investments in a city’s public transportation system are considered critical to the infrastructure that supports the daily needs and quality of life of its residents. Similarly, if we want to support the behavioral health and well-being of Connecticut children and families, we must invest in the infrastructure of the behavioral health system. Because of their unique role in the middle of the care continuum, investing in intermediate levels of care will have positive ripple effects across the entire children’s behavioral health system.

*The behavioral health workforce includes clinical social workers, psychologists, psychiatrists, marriage and family therapists, professional counselors, psychiatric APRNs, addiction counselors, and other behavioral health clinicians. It also includes staff like peer support specialists, aides and technicians, rehabilitation specialists, paraprofessionals, and recovery coaches.

Strengthening the Behavioral Health Workforce for Children, Youth, and Families: A Strategic Plan for Connecticut (CHDI Report, 2023)

CHDI Blog Series: Strengthening CT’s Behavioral Health Workforce (2024)

Making Measures Matter: Use of Measurement-Based Care to Improve Children’s Behavioral Health (CHDI Issue Brief, 2022)

Better than (Usual) Care: Evidence-Based Treatments Improve Outcomes and Reduce Disparities for Children of Color (CHDI Issue Brief, 2019)

When to Adapt: Ensuring Evidence-Based Treatments Work for Children of Diverse Cultural Backgrounds (CHDI Issue Brief, 2023)

Short-Term Solutions to Emergency Department Volume (State of CT Behavioral Health Plan Workgroup Report, 2022)

Urgent Care and Crisis Stabilization Units (State of CT Behavioral Health Plan Workgroup Report, 2022)

"For some CT kids, the mental health care system is struggling." CT Mirror (also published in Hartford Courant), 5/26/24

"CT tries to add workers as children wait weeks for mental health services, new study shows." CT Insider, 3/4/24

|

Aleece Kelly, MPP - Senior Associate akelly@chdi.org |