Issue Brief 89: Building a Strong Foundation

Early childhood is a critical period for building resilience and laying the foundation for healthy development and positive mental health. Experiences in these formative years shape people throughout childhood and into adulthood. This makes the early years a powerful time for both prevention and intervention.

However, as concerns about youth mental health are growing, much of the focus is on older youth. Many of the strategies put forward to address children’s mental health needs, such as increased school-based supports, direct education on mental health topics, and use of telehealth,1 are more likely to address the needs of older children than younger children. Effective and long-lasting solutions must include a focus on early childhood so that all children have the best possible start in life.

Young children can and do experience mental health concerns. One in six children aged 2 to 8-years old have a diagnosed mental, behavioral, or developmental disorder.2 Young children are also exposed to trauma at high rates; it is estimated that 25% of children have experienced a potentially traumatic event, such as witnessing violence or loss of a loved one, by age 4.3 Despite the prevalence of mental health concerns among young children, they are less likely to receive intervention and treatment than older children.

This issue brief identifies effective strategies for strengthening promotion and prevention efforts and ensuring access to high-quality mental health services for young children.

Young children’s mental health centers on strengthening relationships with caregivers

Prevention is always preferable to intervention. All children benefit when those around them (parents, caregivers, educators, and pediatricians) understand how to foster healthy social and emotional development and strong relationships. In fact, well-timed sensitive responses from caring adults in supportive natural environments can prevent the need for intervention in many cases. When intervention is needed, it should be delivered early, effectively, and at a developmentally appropriate level.

Assessing, diagnosing, and treating young children requires specific clinical skills and training.4 Mental health and trauma-related symptoms can look very different in young children. Specific screening and assessment tools, developed and validated for use with younger children, are often needed. Treatment delivery approaches must accommodate the limited language and communication skills of young children, requiring clinicians who understand child development and can tailor approaches to the age and stage of the child.

Caregivers are always important to youth development, but very young children are entirely dependent on them. The most effective treatments for young children are rooted in attachment theory and primarily aim to strengthen the child-caregiver relationship.5 Rather than focusing on the individual child, clinicians need the skills to effectively partner with adult caregivers and bolster the caregiving system.

Intervening early saves time, money, and resources

Early childhood is a critical time to support mental health. Issues that can be resolved with a “light touch” intervention early in life become far more intensive and costly to address later. Untreated mental health disorders ultimately lead to increased expenditures in child welfare, juvenile justice, and substance use and recovery.

On the other hand, early interventions have been shown to return young children to a positive developmental trajectory and are a wise financial investment, resulting in significant future cost savings.6 Child-Parent Psychotherapy, for example, has been demonstrated to return $13.82 in benefits for every $1 in cost to deliver the treatment.7 In short, missing the opportunity to intervene early is costly, in terms of dollars expended, service system burden, and most importantly, compromised well-being.

There is a decline in young children receiving services

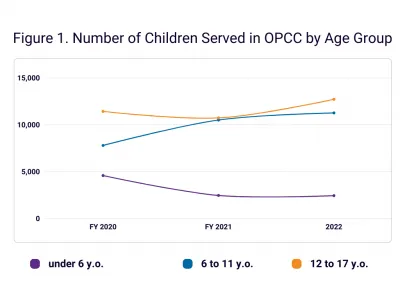

In Connecticut, there has been a marked decline in young children receiving services in the state’s network of Outpatient Psychiatric Clinics for Children (OPCCs), which collectively serve 25,000 children annually. Through FY20, 18% of children receiving services in OPCCs were under 6 years old. Over the past two years, the percentage of young children receiving OPCC services dropped to 10%, as illustrated in Figure 1:

This trend stands in contrast to the overall increase in children seeking services in OPCCs in Connecticut and data showing a growing need for services nationally. It is unclear why fewer young children are being brought to services since COVID, but it is important to investigate the widening gap and identify opportunities to connect the families of young children to care.

Connecticut has begun to build a network of effective treatments for young children

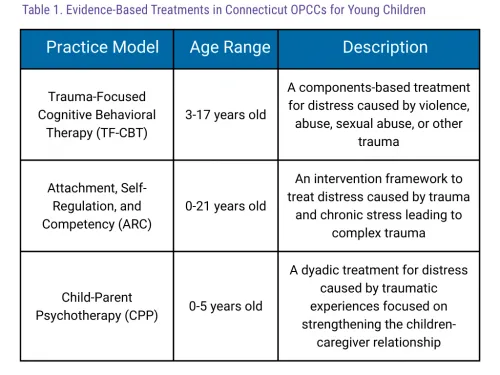

Connecticut has made significant investments in evidence-based treatments (EBTs) for children. Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT), an EBT that helps children recover from upsetting thoughts, feelings, and behaviors associated with trauma exposure, has been offered in Connecticut’s outpatient clinics since 2007. More than 11,000 children have been served to date and those completing treatment demonstrate excellent clinical outcomes.

TF-CBT can be provided to children as young as 3 years old. When young children receive TF-CBT, their rates of completion and symptom improvement are comparable to their older counterparts. However, children under 6 make up only 3-4% of those receiving TF-CBT each year in Connecticut agencies.

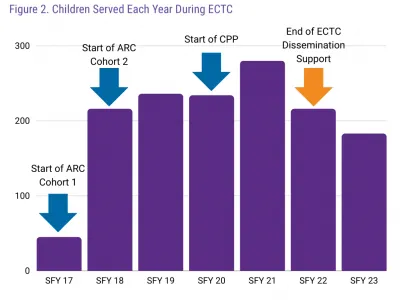

The Early Childhood Trauma Collaborative (ECTC) was formed in 2016 to expand trauma-focused treatments and services for children ages 0-7 in Connecticut. Led by CHDI and funded by SAMHSA as part of the National Child Traumatic Stress Network, ECTC introduced Attachment, Self-Regulation, and Competency (ARC) and Child-Parent Psychotherapy (CPP) into the service array. Through three Learning Collaboratives, ECTC trained 217 clinicians across 16 agencies in either ARC or CPP. ECTC also trained nearly 1,000 early childhood educators and other professionals in the signs and symptoms of trauma to better support children and families and connect them to care.

By the final year of ECTC, over 850 children had received treatment in ARC or CPP. Children completing treatment experienced significant reductions in trauma symptoms and increases in functioning. Caregivers also demonstrated significant reductions in trauma symptoms, depression, and parenting stress. Analyses showed that the treatment worked equally well for children and families, regardless of race and ethnicity.

ECTC was successful in introducing effective treatments for young children, but once the grant funding ended, the number of children served has decreased, as illustrated in Figure 2. The number of children receiving ARC or CPP fell 34.6% since FY21, the last year of grant training and dissemination activities.

Coordination and training across child-serving sectors is needed to support the mental health of young children

Pediatric providers, early care and education staff, and behavioral health clinicians all play an important role in early childhood mental health promotion, prevention, early intervention, and treatment. The early care and education workforce is extremely overburdened and understaffed, which is exacerbated by increases in young children’s behavior issues and mental health needs.8

Early childhood educators and other practitioners need additional funding and supports to help them respond to the needs of children in their care. They are also best positioned, along with pediatricians, to detect concerns and make referrals when necessary. Routine screening helps identify children who need enhanced support early so they can get connected to clinical treatments before concerns worsen.

The referral process is strengthened when early childhood providers have confidence that clinicians deliver high-quality and developmentally appropriate care. ECTC began building these competencies in Connecticut’s behavioral health workforce, but there is a need for increased training on child development and the basics of infant and early childhood mental health among a larger segment of clinical providers. Agencies also need to maintain the capacity to deliver specialized evidence-based treatment to young children to ensure long-term access specific to the needs of this age group.

The behavioral health workforce has been stretched thin due to the increase in need, staff burnout, and chronic underfunding of services both nationally and in Connecticut. In the midst of these challenges, identifying more children who need services might at first seem counterintuitive. This is understandable, but ultimately short-sighted. Failing to identify the behavioral health needs of young children and connect them to treatment does not reduce the demand for services; it simply delays and exacerbates it. This delay comes at the cost of children and families who struggle for longer without support in the intervening years. Delaying treatment also strains the future workforce as providers continue to see more children with more intense needs.

Recommendations to Support Early Childhood Mental Health

To support early childhood mental health, the following recommendations for improving prevention, early intervention, and treatment are made:

Increase awareness about early childhood mental health

Those who work closely with young children and have the best opportunity to shape their environments need to have easy access to information on the promotion of early childhood mental health.

- Build on what has worked with older children: Young children are different than their older counterparts, but thoughtful adaptations to existing resources can extend their reach. One example of this is Gizmo’s Pawsome Guide to Mental Health, a widely used curriculum in Connecticut’s elementary schools. It was adapted for younger audiences by CHDI, OEC, UConn School of Social Work, DMHAS, and United Way through support from CDC. There is a resource guide for families, educators, and home visitors as well as an activity book for young children. As resources and solutions are created to address children’s mental health needs, developers should look for ways to extend their reach to younger audiences

- Develop a “common understanding” across workforces through shared trainings: The state should develop trainings on early childhood mental health that are shared and easily accessed across professional roles In an increasingly virtual world. Developing high-quality and interactive online trainings is a priority in reaching workforces that have limited time but high demand for strategies and approaches to working with young children.

Compensate early childhood educators fairly

Those who work with children each day provide the beneficial experiences that help shape development and set children on more positive trajectories. This has profound impacts not only for individual children and families but for systems and society. And yet, they often make low wages that are not on par with teachers with similar experience and degrees but who work with older youth. Policies to increase the pay in the field, like those put forth by advocates in the state, are needed to support the workforce that supports children during this pivotal time period.

Support early childhood providers and pediatricians in screening for trauma and mental health concerns

Universal screening helps detect concerns that might otherwise be missed. The state should support providers to screen young children by ensuring training is available and that providers are reimbursed for screening. Trauma ScreenTIME is one resource to support child-serving professionals in implementing trauma screening.

Ensure treatments for young children are available when needed

When families of young children do seek treatment, they need treatment that works.

- Provide foundational training in child development and infant and early childhood mental health to all clinicians working with children.

- Support sustainment and dissemination of EBT models for young children at community mental health providers serving children and families. Efforts should build on the strong foundation that already exists with TF-CBT, ARC, CPP which have demonstrated success in helping young children in Connecticut.

- Ensure equitable access, quality, and outcomes: As capacity is built to better respond to the mental health needs of young children, access to and experience with these treatments should be equitable for all groups. The models selected need to have been shown effective with the agency population they will serve. EBTs can reduce treatment disparities9 and the outcomes of ECTC showed equivalent outcomes across groups. Data collection and quality improvement activities focusing on race, ethnicity, and language status are needed to make certain all children are getting the best possible treatment.

This Issue Brief was prepared by Kellie Randall, PhD and Jason Lang, PhD. For more information, visit www.chdi.org or contact Kellie Randall.

- Abramson, A. (2022). Children’s mental health is in crisis: As pandemic stressors continue, kids’ mental health needs to be addressed in schools. Trends Report, 53(1), 69.

- Cree RA, Bitsko RH, Robinson LR, Holbrook JR, Danielson ML, Smith DS, Kaminski JW, Kenney MK, Peacock G. Health care, family, and community factors associated with mental, behavioral, and developmental disorders and poverty among children aged 2–8 years — United States, 2016. MMWR, 2018;67(5):1377-1383.

- Briggs-Gowan, M. J., Ford, J. D., Fraleigh, L., McCarthy, K., & Carter, A. S. (2010). Prevalence of exposure to potentially traumatic events in a healthy birth cohort of very young children in

- Zeanah CH, Boris NW. Disturbances and disorders of attachment in early childhood. In: Handbook of infant mental health, 2nd edition Guilford Press; (2000).

- Shafi, R. M. A., Bieber, E. D., Shekunov, J., Croarkin, P. E., & Romanowicz, M. (2019). Evidence based dyadic therapies for 0- to 5-year-old children with emotional and behavioral difficulties. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 677. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00677

- Oppenheim, J. & Bartlett, J.D. (2022). Cost-effectiveness of Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Treatment. Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Technical Assistance Center.

- Washington State Institute for Public Policy (2019). Child-Parent Psychotherapy. https://www.wsipp.wa.gov/BenefitCost/Program/263#:~:text=Child%2DParent%20Psychotherapy%20is%20

- Stein, R., Garay, M., & Nguyen, A. (2022). It Matters: Early Childhood Mental Health, Educator Stress, and Burnout. Early childhood education journal, 1–12. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-022-01438-8

- Lang, J. M., Lee, P., Connell, C. M., Marshall, T., & Vanderploeg, J. J. (2021). Outcomes, evidence-based treatments, and disparities in a statewide outpatient children’s behavioral health system. Children and Youth Services Review, 120, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105729

Early childhood trauma initiatives

Learn more about CHDI's work to expand support for early childhood trauma identification and treatment.

Evidence-based trauma treatment

CHDI and DCF are expanding trauma-informed treatments across Connecticut.