Share This Publication

Issue Brief 83: Evidence-Based Treatments are Effective for Children in the Child Welfare System: Connecticut’s Family First Prevention Services Plan Can Expand Access to Effective Care

December 16, 2021

Evidence-Based Treatments are Effective for Children in the Child Welfare System:

Connecticut’s Family First Prevention Services Plan Can Expand Access to Effective Care

Each year in Connecticut, over 18,000 children come into contact with the child welfare system due to confirmed or suspected abuse or neglect.1 Children in the child welfare system are more likely than other children to have mental health conditions2 and to have experienced potentially traumatic events (e.g., physical or sexual abuse, family violence)3 or other adversities.4 The COVID-19 pandemic has stressed many families in the form of disruptions to routines of daily life, increased isolation, financial hardship, and illness or death of loved ones.5 Emerging evidence suggests that COVID poses particular risks for children living in unsafe home environments who now have fewer supports and limited exposure to mandated reporters.6 Now more than ever, there is a clear and pressing need for effective behavioral health treatments for youth in the child welfare system. Fortunately, Connecticut is working to address this need by expanding services through the Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA). Connecticut has long been a leader in increasing access to evidence-based treatments (EBTs) and improving outcomes for children. Connecticut’s Family First Prevention Services plan provides an opportunity to build an array of effective behavioral health treatments and other services for those children most at-risk for foster home placement with the goal of keeping families together. Connecticut’s documented success with EBTs will be instrumental in the implementation and delivery of these new services.

Connecticut Offers Several EBTs for Children

EBTs are treatments that have been rigorously tested and found to be more effective than usual care. EBTs have been developed for a wide range of common behavioral health conditions, including traumatic stress, anxiety, depression, and conduct problems. Connecticut, led by the Department of Children and Families (DCF) and the Court Support Services Division of the Judicial Branch (CCSD), has made significant investments in EBTs for children in a range of setting from outpatient clinics to intensive in-home services. DCF and CSSD have partnered with CHDI to disseminate multiple EBTs throughout the State. A list of providers offering EBTs disseminated in Connecticut by CHDI can be found at https://ebp.dcf.ct.gov/ebpsearch. In the child welfare system, DCF has partnered with CHDI and outpatient behavioral health providers through the federally funded CONCEPT initiative to expand EBT access and advance a more trauma-informed child welfare system.

Figure 1. Selected Evidence-Based Treatments Available in Connecticut

A recent study analyzed several EBTs being delivered in outpatient settings across Connecticut and found improved outcomes for all children, as well as reduced racial and ethnic disparities as compared to usual care.7 One such EBT is Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) which has more than 15 studies demonstrating its effectiveness for children exposed to trauma, including children who have experienced abuse and neglect, been placed in foster care, and those in residential or group home settings. The model is listed as a Promising Practice on the Title IV-E Prevention Services Clearinghouse. TF-CBT was of particular interest as DCF, in partnership with CHDI and outpatient agencies, supported its dissemination across the state.

However, traumatic stress is not the only reason for which children in the child welfare system might require treatment, and Connecticut’s outpatient network offers at least 15 other EBTs. Connecticut’s Family First Prevention Services plan includes additional EBTs, some of which are established and others that are emerging or would be new to the state. Together these would provide a continuum of services to address not only mental health, but also substance abuse prevention and parenting skills.

EBTs are Improving Outcomes for Child Welfare-Involved Children and Families

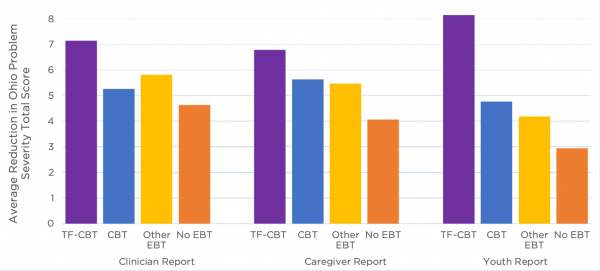

Outcomes were measured using the Ohio Scales for Problem Severity, using caregiver, clinician, and child report. These preliminary analyses show that child welfare-involved children who received EBTs experienced better outcomes than those who did not.

EBT use was high for child welfare-involved children.

- Children with child welfare system-involvement were slightly more likely than those without involvement to receive an EBT (47% vs. 44%)

- Compared to children without involvement, child welfare system-involved children were 2.4 times more likely to receive TF-CBT; they were equally or less likely to receive all other EBTs.

- 40% of all children who received TF-CBT had child welfare system involvement, although they made up only 22% of outpatient cases.

- Children 6 and under were more likely to have child welfare system-involvement but were significantly less likely to receive an EBT.

Child welfare-involved children who received an EBT had greater improvement in problem severity than those who received No EBT.

- Both TF-CBT and CBT outperformed No EBT on all reports of improvement in problem severity

- TF-CBT was associated with 57%-61% greater improvement than No EBT according to clinician and caregiver reports.

- Children who received TF-CBT reported 165% greater improvement in problem severity compared to No EBT and 65% to 90% improvement compared to other EBTs.

Figure 2.

Recommendations for Ensuring Connecticut’s Most Vulnerable Children Get the Most Effective Services

While nearly half of youth involved in the child welfare system who received outpatient treatment received an EBT, estimates suggest a much greater need for access to EBTs among all youth, including youth in the child welfare system. Some children will receive treatment, including EBTs, in settings other than outpatient, such as in-home services. But outpatient settings are where the vast majority of children receiving mental health treatment get their care, and Connecticut’s network of outpatient providers offer broad and accessible services across the state with EBTs that have demonstrated improved outcomes. Supporting EBTs across home, outpatient, and school settings and improving access to youth in the child welfare system can help ensure some of Connecticut’s most vulnerable children get the most effective services. Connecticut’s Family First Prevention Services plan, once approved, provides an opportunity to expand access to EBTs for children in a range of settings. The following recommendations will help to ensure that Connecticut fully leverages new opportunities for EBTs available as a result of FFPSA implementation.

- Strengthen collaboration and communication between DCF and community providers to improve access to EBTs for children in the child welfare system. EBT providers can regularly reach out to their local DCF offices to provide information on the EBTs and services they offer. DCF offices can designate a “point person” to serve as the primary contact with community providers to facilitate referrals and help ensure DCF staff know about the EBTs. Coordination between local child welfare and mental health service providers, which might take the form of shared meetings, joint trainings, streamlined referrals using technology, and clear communication channels can help ensure both systems have the information they need to connect children with the best services to meet their needs. Once connections are made, data sharing across systems will be needed to document whether EBT treatment also results in improvement in child welfare outcomes, such as maltreatment recurrence or out-of-home placements. These cross-system collaborations are especially crucial given communities of color are disproportionately represented in the child welfare system, and EBTs may reduce racial disparities in treatment outcomes.

- Train clinicians in using EBTs with child welfare system-involved youth. The high rates of TF-CBT and other trauma-focused treatments can be attributed to concerted efforts to ensure children in the child welfare system had access to the interventions through initiatives like CONCEPT. However, trauma treatment is not the only need among children in the child welfare system who have a range of behavioral health needs and conditions and require access to treatments that work for any and all of these diverse conditions. Modular Approach to Therapy for Children with Anxiety, Depression, Trauma, or Conduct Problems (MATCH-ADTC) is an example of this type of EBT. MATCH-ADTC is available in Connecticut, but relatively few children with child welfare system involvement have received it. Training and consultation for clinicians on using existing EBTs with child welfare system-involved youth and families may further increase treatment options. The new and emerging EBTs the FFPSA plan proposes to deliver stand to benefit from the robust infrastructure the state already has in place for disseminating EBTs. The state’s experience with introducing and sustaining EBTs, through Learning Collaboratives and ongoing quality improvement consultation, can be adapted to help ensure successful implementation of the newer EBTs in the FFPSA plan.

- Invest in EBTs for young children. Nationally and in Connecticut, younger children are more likely to have child welfare system involvement and to be at risk for removal from the home; however, these results found that younger children in the child welfare system were less likely to receive an EBT than older children, which is a gap that must be addressed. CHDI’s Early Childhood Trauma Collaborative is a SAMHSA-funded initiative that disseminated two EBTs for very young children (0-6 years): Child Parent Psychotherapy (CPP) and Attachment, Self-Regulation, and Competency (ARC). These models are now available at 11 provider agencies and have been received by over 650 children and families, 35% of whom have child welfare involvement. As federal support for these models ends, sustaining and expanding EBTs for young children is critical. The state should support sustainability of these developmentally-appropriate, trauma-informed services for the youngest children, including those in the child welfare system.

References

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. (2021). Child Maltreatment 2019. Available from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment.

- Burns, B. J., Phillips, S. D., Wagner, H. R., Barth, R. P., Kolko, D. J., Campbell, Y., & Landsverk, J. (2004). Mental health need and access to mental health services by youths involved with child welfare: A national survey. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(8), 960-970.

- Greeson, J. K., Briggs, E. C., Kisiel, C. L., Layne, C. M., Ake III, G. S., Ko, S. J., ... & Fairbank, J. A. (2011). Complex trauma and mental health in children and adolescents placed in foster care: Findings from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Child welfare, 90(6), 91.

- Garcia, A.R., Gupta, M., Greeson, J. K., Thompson, A., & DeNard, C. (2017). Adverse childhood experiences among youth reported to child welfare: Results from the national survey of child & adolescent wellbeing. Child Abuse & Neglect, 70, 292-302.

- Patrick, S. W., Henkhaus, L. E., Zickafoose, J. S., Lovell, K., Halvorson, A., Loch, S., ... & Davis, M. (2020). Well-being of parents and children during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national survey. Pediatrics, 146(4).

- Cohen, R. I. S., & Bosk, E. A. (2020). Vulnerable youth and the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics, 146(1).

- Lang, J. M., Lee, P., Connell, C. M., Marshall, T., & Vanderploeg, J. J. (2021). Outcomes, evidence-based treatments, and disparities in a statewide outpatient children’s behavioral health system. Children and Youth Services Review, 120, 105729.

This Issue Brief was prepared by Kellie Randall, Ph.D., Director of Quality Improvement. For more information, contact Dr. Randall at randall@uchc.edu or visit www.chdi.org. Search CHDI’s Evidence-Based Practice Directory to find sites offering some of the evidence-based practices available in Connecticut.

Download pdf